Hallmarks of Aging: Difference between revisions

| Line 184: | Line 184: | ||

|Telomere shortening is observed during normal aging in humans and mice{{pmid|17876321}}. | |Telomere shortening is observed during normal aging in humans and mice{{pmid|17876321}}. | ||

|Excessive telomere attrition due to stress or genetic factors accelerates cellular aging and the onset of age-related pathologies{{pmid|22426077}}. | |Excessive telomere attrition due to stress or genetic factors accelerates cellular aging and the onset of age-related pathologies{{pmid|22426077}}. | ||

|Maintaining telomere length through telomerase activation or shelterin integrity can delay aging and extend lifespan, as shown in mouse models and suggested by human epidemiological studies{{pmid|21113150}} | |Maintaining telomere length through telomerase activation or shelterin integrity can delay aging and extend lifespan, as shown in mouse models and suggested by human epidemiological studies{{pmid|21113150}}{{pmid|22585399}}. | ||

|Telomere shortening is associated with a variety of human diseases, including pulmonary fibrosis, dyskeratosis congenita, and aplastic anemia, often linked to deficiencies in telomerase or shelterin components{{pmid|22965356}}. | |Telomere shortening is associated with a variety of human diseases, including pulmonary fibrosis, dyskeratosis congenita, and aplastic anemia, often linked to deficiencies in telomerase or shelterin components{{pmid|22965356}}. | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 197: | Line 197: | ||

* Overexpression of SIRT1 improves aspects of health during aging but does not increase longevity{{pmid|20975665}} | * Overexpression of SIRT1 improves aspects of health during aging but does not increase longevity{{pmid|20975665}} | ||

* Overexpression of SIRT3 reverse the regenerative capacity of aged stem cells{{pmid|23375372}} | * Overexpression of SIRT3 reverse the regenerative capacity of aged stem cells{{pmid|23375372}} | ||

* Overexpressing ''SIRT6'' in mice have a longer lifespan | * Overexpressing ''SIRT6'' in mice have a longer lifespan{{pmid|22367546}} | ||

|Disorders in histone modification are linked with various aging-related conditions, implicating altered gene expression and protein function{{pmid|22291607}}. | |Disorders in histone modification are linked with various aging-related conditions, implicating altered gene expression and protein function{{pmid|22291607}}. | ||

|- | |- | ||

Revision as of 01:41, 5 January 2024

Aging is characterized by a progressive loss of physiological integrity, leading to impaired function and increased vulnerability to death. The hallmarks of aging are the types of biochemical changes that occur in all organisms that experience biological aging and lead to a progressive loss of physiological integrity, impaired function and, eventually, death. They were first listed in a landmark paper in 2013[1] to conceptualize the essence of biological aging and its underlying mechanisms.

Criteria

Each hallmark was chosen to try to fulfill the following criteria:[1]

- manifests during normal aging;

- experimentally increasing it accelerates aging;

- experimentally amending it slows the normal aging process and increases healthy lifespan.

These conditions are met to different extents by each of these hallmarks. The last criterion is not present in many of the hallmarks, as science has not yet found feasible ways to amend these problems in living organisms.

Overview

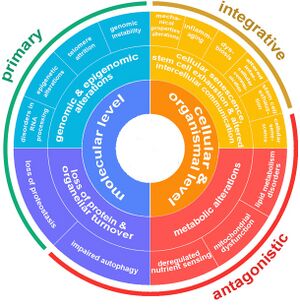

Aging is a complex process characterized by a gradual decline in physiological function. The hallmarks of aging are classified into three categories, each describing different aspects of the aging process:

- Primary Hallmarks: These are considered the main causes of cellular damage leading to aging. They are the initiating factors that, over time, drive the functional decline seen in aging cells and tissues.

- Antagonistic Hallmarks: These hallmarks are the response to the damage caused by the primary hallmarks. Initially, they may be compensatory or protective, but when chronic or excessive, they become deleterious, contributing to the aging process.

- Integrative Hallmarks: These hallmarks are the culprits of the phenotype of aging. They result from a combination of the primary and antagonistic hallmarks and are ultimately responsible for the functional decline in tissues and organs seen in aging.

The Nine Hallmarks of Aging (2013)

The nine hallmarks of aging were originally conceptualized by López-Otín and colleagues in 2013[1]. Since that it has served as a foundational paradigm for aging research for a decade until it has been revised in 2022. The original 9 landmarks were defined as follows:

| # | Hallmark | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Genomic Instability | Primary Hallmarks

(causes damage) |

| 2 | Telomere Attrition | |

| 3 | Epigenetic Alterations | |

| 4 | Loss of Proteostasis | |

| 5 | Deregulated Nutrient Sensing | Antagonistic Hallmarks

(responses to damage) |

| 6 | Mitochondrial Dysfunction | |

| 7 | Cellular Senescence | |

| 8 | Stem Cell Exhaustion | Integrative Hallmarks

(culprits of the phenotype) |

| 9 | Altered Intercellular Communication |

Five New Hallmarks of Aging (2022)

While these nine hallmarks have significantly advanced our understanding of aging and its relation to age-related diseases, recent critiques and evolving scientific evidence have prompted the scientific community to reconsider and expand this framework.[4] To address this, a symposium titled “New Hallmarks of Ageing” was held in Copenhagen on March 2022, where leading experts gathered to discuss potential additions and recontextualizations of these aging hallmarks. The symposium highlighted the critical need for an expanded, inclusive paradigm that encompasses newly identified processes contributing to aging. The discussions suggested the integration of five additional hallmarks:

- compromised autophagy

- dysregulation in RNA splicing

- inflammation

- loss of cytoskeleton integrity

- disturbance of the microbiome (dysbiosis)

These potential new hallmarks, along with the original nine, underscore a more comprehensive understanding of the aging process, acknowledging its multifaceted nature and its profound implications for human health and longevity.[5]

The Twelve Hallmarks of Aging (2023)

| Level | Hallmark | Description | Proposed Year |

Category | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Level |

|

Genomic instability | Accumulation of DNA damage over time leading to cellular dysfunction. | 2013 | Primary Hallmarks (causes damage) |

|

Telomere attrition | Reduction in the length of telomeres leading to cellular aging. | 2013 | ||

|

Epigenetic alterations | Changes in DNA methylation and histone modification affecting gene expression. | 2013 | ||

|

Loss of proteostasis | Disruption in protein folding and stability leading to cell damage. | 2013 | ||

|

Disabled autophagy | Impaired cellular maintenance through the consumption of own components. | 2021[6] | Antagonistic Hallmarks (responses to damage) | |

| Cellular & Organismal Level |

|

Deregulated nutrient sensing | Alterations in nutrient sensing pathways affecting metabolism and aging. | 2013 | |

|

Mitochondrial dysfunction | Decrease in mitochondrial efficiency and increase in oxidative stress. | 2013 | ||

|

Cellular senescence | Accumulation of non-dividing, dysfunctional cells secreting harmful factors. | 2013 | ||

|

Stem cell exhaustion | Decline in the regenerative capacity of stem cells affecting tissue repair. | 2013 | Integrative Hallmarks (culprits of the phenotype) | |

|

Dysbiosis

(Microbiome disturbance) |

Changes in gut microbiome affecting health and aging. | |||

|

Chronic inflammation

(Inflammaging) |

Systemic inflammation contributing to aging and related diseases. | 2023[7] | ||

|

Altered intercellular communication | Changes in cellular communication leading to inflammation and tissue dysfunction. | 2013 | ||

Potential Hallmarks of Aging

|

Altered mechanical properties | Changes in cellular and extracellular structure affecting tissue function. | |

|

Splicing dysregulation

(Dysregulation in RNA splicing) |

Impaired RNA construction from DNA, leading to cellular dysfunction. | 2019[8] |

The Hallmarks in Detail

| Hallmark | Background | Manifests during normal aging | Experimentally increasing it accelerates aging | Experimentally amending it slows the normal aging process and increases healthy lifespan. | Associated human diseases | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Genomic instability | Damange in the DNA are formed mainly through oxidative stress and environmental factors.[9] A number of molecular processes work continuously to repair this damage.[10] | DNA damage accumulates over time[11] | Deficient DNA repair causes premature aging[12] | Increased DNA repair facilitates greater longevity[12] | |

|

Telomere attrition | Telomere attrition refers to the progressive shortening of telomeres, which are protective sequences at the ends of chromosomes. This occurs due to the inability of DNA polymerases to completely replicate the ends of linear DNA, and the absence of telomerase in most somatic cells. Shortened telomeres lead to cellular aging and reduced regenerative capacity, manifesting as replicative senescence or Hayflick limit[13]. Shelterins protect telomeres but may mask damage leading to persistent DNA damage and cellular stress[14]. Dysfunctions in telomere maintenance are linked to various age-related diseases[15]. | Telomere shortening is observed during normal aging in humans and mice[16]. | Excessive telomere attrition due to stress or genetic factors accelerates cellular aging and the onset of age-related pathologies[17]. | Maintaining telomere length through telomerase activation or shelterin integrity can delay aging and extend lifespan, as shown in mouse models and suggested by human epidemiological studies[18][19]. | Telomere shortening is associated with a variety of human diseases, including pulmonary fibrosis, dyskeratosis congenita, and aplastic anemia, often linked to deficiencies in telomerase or shelterin components[15]. |

|

Epigenetic alterations | Histone modifications are a type of epigenetic alteration that play a crucial role in regulating gene expression. Histones are proteins around which DNA is wrapped in eukaryotic cells, forming a structure known as a nucleosome. These modifications occur primarily at the tails of histone proteins and influence how tightly or loosely DNA is wound around the histones, affecting the accessibility of the DNA to various cellular machinery for processes like transcription, replication, and repair. | Chemical changes to histone proteins after they are formed can activate or silence gene expression and regulate the aging process.[20] | Sirtuins influence histone modifications:

|

Disorders in histone modification are linked with various aging-related conditions, implicating altered gene expression and protein function[25]. | |

| DNA methylation shift: DNA methylation is a biochemical process involving the addition of a methyl group to the DNA molecule, specifically to the cytosine or adenine DNA nucleotides. This process is a form of epigenetic modification, which means it can affect gene expression and function without changing the DNA sequence itself. | DNA methylation generally decreases with age in certain human and mouse tissues or cell cultures.[26][27][28][29] The loss of methylation in CD4+ T cells is proportional to age.[27] | No direct evidence yet that altering DNA methylation patterns extends lifespan. | No direct evidence yet that altering DNA methylation patterns extends lifespan. | Progeroid syndromes exhibit DNA methylation patterns similar to normal aging, suggesting a link with aging-related diseases[30][31]. | ||

| Chromatin remodeling in the context of epigenetic alterations refers to the dynamic modification of the chromatin architecture to regulate access to genetic information in the DNA. Chromatin, which consists of DNA wrapped around histone proteins, can be altered or remodeled in various ways to either condense and silence gene regions or relax and activate them. This remodeling is a crucial mechanism for controlling gene expression, replication, repair, and other essential cellular processes. | Global canonical histone loss is regarded as a common feature of aging from yeast to humans.[32][33][34] | Flies with loss-of-function mutations in HP1α (a key chromosomal protein) have a shortened lifespan.[25] | Overexpression of HP1α extends longevity in flies and delays the muscular deterioration characteristic of old age.[25] | |||

| Chromatin remodeling: | Chromatin remodeling, involving chromosomal proteins and factors like HP1α and Polycomb group proteins, changes with age. These alterations contribute to global heterochromatin loss and affect chromosomal stability[35] [36]. | Disruptions in chromatin remodeling factors can accelerate aging, as shown in models with loss-of-function mutations in key proteins like HP1α[25]. | Manipulating chromatin remodeling components may slow aging, as indicated by the extended lifespan in flies with overexpressed heterochromatin proteins[25]. | Alterations in chromatin remodeling are implicated in various age-related diseases and conditions, impacting genomic stability and cellular functionality[35]. | ||

|

Loss of proteostasis | |||||

|

Disabled autophagy | |||||

|

Deregulated nutrient sensing | |||||

|

Mitochondrial dysfunction | |||||

|

Cellular senescence | |||||

|

Stem cell exhaustion | |||||

|

Dysbiosis

(Microbiome disturbance) |

|||||

|

Chronic inflammation

(Inflammaging) |

|||||

|

Altered intercellular communication | |||||

History

- 2013 The scientific journal Cell published the article "The Hallmarks of Aging", that was translated to several languages and determined the directions of many studies.[1]

- 2022 It was proposed to expand the list of the nine hallmarks of aging with five more.[5][37]

- 2023 In a paywalled review, the authors of a heavily cited paper on the hallmarks of aging update the set of proposed hallmarks after a decade.[38] A review with overlapping authors merge or link various hallmarks of cancer with those of aging.[39]

Todo

- 2013, The hallmarks of aging [1]

- 2023, Chronic inflammation and the hallmarks of aging [7]

- 2023, Aging Hallmarks and Progression and Age-Related Diseases: A Landscape View of Research Advancement [2]

- 2022, Biological mechanisms of aging predict age-related disease co-occurrence in patients [3]

- https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-023-02024-y

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 López-Otín C et al.: The hallmarks of aging. Cell 2013. (PMID 23746838) [PubMed] [DOI] [Full text] Aging is characterized by a progressive loss of physiological integrity, leading to impaired function and increased vulnerability to death. This deterioration is the primary risk factor for major human pathologies, including cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular disorders, and neurodegenerative diseases. Aging research has experienced an unprecedented advance over recent years, particularly with the discovery that the rate of aging is controlled, at least to some extent, by genetic pathways and biochemical processes conserved in evolution. This Review enumerates nine tentative hallmarks that represent common denominators of aging in different organisms, with special emphasis on mammalian aging. These hallmarks are: genomic instability, telomere attrition, epigenetic alterations, loss of proteostasis, deregulated nutrient sensing, mitochondrial dysfunction, cellular senescence, stem cell exhaustion, and altered intercellular communication. A major challenge is to dissect the interconnectedness between the candidate hallmarks and their relative contributions to aging, with the final goal of identifying pharmaceutical targets to improve human health during aging, with minimal side effects.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Tenchov R et al.: Aging Hallmarks and Progression and Age-Related Diseases: A Landscape View of Research Advancement. ACS Chem Neurosci 2023. (PMID 38095562) [PubMed] [DOI] Aging is a dynamic, time-dependent process that is characterized by a gradual accumulation of cell damage. Continual functional decline in the intrinsic ability of living organisms to accurately regulate homeostasis leads to increased susceptibility and vulnerability to diseases. Many efforts have been put forth to understand and prevent the effects of aging. Thus, the major cellular and molecular hallmarks of aging have been identified, and their relationships to age-related diseases and malfunctions have been explored. Here, we use data from the CAS Content Collection to analyze the publication landscape of recent aging-related research. We review the advances in knowledge and delineate trends in research advancements on aging factors and attributes across time and geography. We also review the current concepts related to the major aging hallmarks on the molecular, cellular, and organismic level, age-associated diseases, with attention to brain aging and brain health, as well as the major biochemical processes associated with aging. Major age-related diseases have been outlined, and their correlations with the major aging features and attributes are explored. We hope this review will be helpful for apprehending the current knowledge in the field of aging mechanisms and progression, in an effort to further solve the remaining challenges and fulfill its potential.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Fraser HC et al.: Biological mechanisms of aging predict age-related disease co-occurrence in patients. Aging Cell 2022. (PMID 35259281) [PubMed] [DOI] [Full text] Genetic, environmental, and pharmacological interventions into the aging process can confer resistance to multiple age-related diseases in laboratory animals, including rhesus monkeys. These findings imply that individual mechanisms of aging might contribute to the co-occurrence of age-related diseases in humans and could be targeted to prevent these conditions simultaneously. To address this question, we text mined 917,645 literature abstracts followed by manual curation and found strong, non-random associations between age-related diseases and aging mechanisms in humans, confirmed by gene set enrichment analysis of GWAS data. Integration of these associations with clinical data from 3.01 million patients showed that age-related diseases associated with each of five aging mechanisms were more likely than chance to be present together in patients. Genetic evidence revealed that innate and adaptive immunity, the intrinsic apoptotic signaling pathway and activity of the ERK1/2 pathway were associated with multiple aging mechanisms and diverse age-related diseases. Mechanisms of aging hence contribute both together and individually to age-related disease co-occurrence in humans and could potentially be targeted accordingly to prevent multimorbidity.

- ↑ Gems D & de Magalhães JP: The hoverfly and the wasp: A critique of the hallmarks of aging as a paradigm. Ageing Res Rev 2021. (PMID 34271186) [PubMed] [DOI] [Full text] With the goal of representing common denominators of aging in different organisms López-Otín et al. in 2013 described nine hallmarks of aging. Since then, this representation has become a major reference point for the biogerontology field. The template for the hallmarks of aging account originated from landmark papers by Hanahan and Weinberg (2000, 2011) defining first six and later ten hallmarks of cancer. Here we assess the strengths and weaknesses of the hallmarks of aging account. As a checklist of diverse major foci of current aging research, it has provided a useful shared overview for biogerontology during a time of transition in the field. It also seems useful in applied biogerontology, to identify interventions (e.g. drugs) that impact multiple symptomatic features of aging. However, while the hallmarks of cancer provide a paradigmatic account of the causes of cancer with profound explanatory power, the hallmarks of aging do not. A worry is that as a non-paradigm the hallmarks of aging have obscured the urgent need to define a genuine paradigm, one that can provide a useful basis for understanding the mechanistic causes of the diverse aging pathologies. We argue that biogerontology must look and move beyond the hallmarks to understand the process of aging.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Schmauck-Medina T et al.: New hallmarks of ageing: a 2022 Copenhagen ageing meeting summary. Aging (Albany NY) 2022. (PMID 36040386) [PubMed] [DOI] [Full text] Genomic instability, telomere attrition, epigenetic alterations, mitochondrial dysfunction, loss of proteostasis, deregulated nutrient-sensing, cellular senescence, stem cell exhaustion, and altered intercellular communication were the original nine hallmarks of ageing proposed by López-Otín and colleagues in 2013. The proposal of these hallmarks of ageing has been instrumental in guiding and pushing forward research on the biology of ageing. In the nearly past 10 years, our in-depth exploration on ageing research has enabled us to formulate new hallmarks of ageing which are compromised autophagy, microbiome disturbance, altered mechanical properties, splicing dysregulation, and inflammation, among other emerging ones. Amalgamation of the 'old' and 'new' hallmarks of ageing may provide a more comprehensive explanation of ageing and age-related diseases, shedding light on interventional and therapeutic studies to achieve healthy, happy, and productive lives in the elderly.

- ↑ Kaushik S et al.: Autophagy and the hallmarks of aging. Ageing Res Rev 2021. (PMID 34563704) [PubMed] [DOI] [Full text] Autophagy, an essential cellular process that mediates degradation of proteins and organelles in lysosomes, has been tightly linked to cellular quality control for its role as part of the proteostasis network. The current interest in identifying the cellular and molecular determinants of aging, has highlighted the important contribution of malfunctioning of autophagy with age to the loss of proteostasis that characterizes all old organisms. However, the diversity of cellular functions of the different types of autophagy and the often reciprocal interactions of autophagy with other determinants of aging, is placing autophagy at the center of the aging process. In this work, we summarize evidence for the contribution of autophagy to health- and lifespan and provide examples of the bidirectional interplay between autophagic pathways and several of the so-called hallmarks of aging. This central role of autophagy in aging, and the dependence on autophagy of many geroprotective interventions, has motivated a search for direct modulators of autophagy that could be used to slow aging and extend healthspan. Here, we review some of those ongoing therapeutic efforts and comment on the potential of targeting autophagy in aging.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Baechle JJ et al.: Chronic inflammation and the hallmarks of aging. Mol Metab 2023. (PMID 37329949) [PubMed] [DOI] [Full text] BACKGROUND: Recently, the hallmarks of aging were updated to include dysbiosis, disabled macroautophagy, and chronic inflammation. In particular, the low-grade chronic inflammation during aging, without overt infection, is defined as "inflammaging," which is associated with increased morbidity and mortality in the aging population. Emerging evidence suggests a bidirectional and cyclical relationship between chronic inflammation and the development of age-related conditions, such as cardiovascular diseases, neurodegeneration, cancer, and frailty. How the crosstalk between chronic inflammation and other hallmarks of aging underlies biological mechanisms of aging and age-related disease is thus of particular interest to the current geroscience research. SCOPE OF REVIEW: This review integrates the cellular and molecular mechanisms of age-associated chronic inflammation with the other eleven hallmarks of aging. Extra discussion is dedicated to the hallmark of "altered nutrient sensing," given the scope of Molecular Metabolism. The deregulation of hallmark processes during aging disrupts the delicate balance between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory signaling, leading to a persistent inflammatory state. The resultant chronic inflammation, in turn, further aggravates the dysfunction of each hallmark, thereby driving the progression of aging and age-related diseases. MAIN CONCLUSIONS: The crosstalk between chronic inflammation and other hallmarks of aging results in a vicious cycle that exacerbates the decline in cellular functions and promotes aging. Understanding this complex interplay will provide new insights into the mechanisms of aging and the development of potential anti-aging interventions. Given their interconnectedness and ability to accentuate the primary elements of aging, drivers of chronic inflammation may be an ideal target with high translational potential to address the pathological conditions associated with aging.

- ↑ Bhadra M et al.: Alternative splicing in aging and longevity. Hum Genet 2020. (PMID 31834493) [PubMed] [DOI] [Full text] Alternative pre-mRNA splicing increases the complexity of the proteome that can be generated from the available genomic coding sequences. Dysregulation of the splicing process has been implicated in a vast repertoire of diseases. However, splicing has recently been linked to both the aging process itself and pro-longevity interventions. This review focuses on recent research towards defining RNA splicing as a new hallmark of aging. We highlight dysfunctional alternative splicing events that contribute to the aging phenotype across multiple species, along with recent efforts toward deciphering mechanistic roles for RNA splicing in the regulation of aging and longevity. Further, we discuss recent research demonstrating a direct requirement for specific splicing factors in pro-longevity interventions, and specifically how nutrient signaling pathways interface to splicing factor regulation and downstream splicing targets. Finally, we review the emerging potential of using splicing profiles as a predictor of biological age and life expectancy. Understanding the role of RNA splicing components and downstream targets altered in aging may provide opportunities to develop therapeutics and ultimately extend healthy lifespan in humans.

- ↑ De Bont R & van Larebeke N: Endogenous DNA damage in humans: a review of quantitative data. Mutagenesis 2004. (PMID 15123782) [PubMed] [DOI] DNA damage plays a major role in mutagenesis, carcinogenesis and ageing. The vast majority of mutations in human tissues are certainly of endogenous origin. A thorough knowledge of the types and prevalence of endogenous DNA damage is thus essential for an understanding of the interactions of endogenous processes with exogenous agents and the influence of damage of endogenous origin on the induction of cancer and other diseases. In particular, this seems important in risk evaluation concerning exogenous agents that also occur endogenously or that, although chemically different from endogenous ones, generate the same DNA adducts. This knowledge may also be crucial to the development of rational chemopreventive strategies. A list of endogenous DNA-damaging agents, processes and DNA adduct levels is presented. For the sake of comparison, DNA adduct levels are expressed in a standardized way, including the number of adducts per 10(6) nt. This list comprises numerous reactive oxygen species and products generated as a consequence (e.g. lipid peroxides), endogenous reactive chemicals (e.g. aldehydes and S-adenosylmethionine), and chemical DNA instability (e.g. depurination). The respective roles of endogenous versus exogenous DNA damage in carcinogenesis are discussed.

- ↑ de Duve C: The onset of selection. Nature 2005. (PMID 15703726) [PubMed] [DOI]

- ↑ Vijg J & Suh Y: Genome instability and aging. Annu Rev Physiol 2013. (PMID 23398157) [PubMed] [DOI] Genome instability has long been implicated as the main causal factor in aging. Somatic cells are continuously exposed to various sources of DNA damage, from reactive oxygen species to UV radiation to environmental mutagens. To cope with the tens of thousands of chemical lesions introduced into the genome of a typical cell each day, a complex network of genome maintenance systems acts to remove damage and restore the correct base pair sequence. Occasionally, however, repair is erroneous, and such errors, as well as the occasional failure to correctly replicate the genome during cell division, are the basis for mutations and epimutations. There is now ample evidence that mutations accumulate in various organs and tissues of higher animals, including humans, mice, and flies. What is not known, however, is whether the frequency of these random changes is sufficient to cause the phenotypic effects generally associated with aging. The exception is cancer, an age-related disease caused by the accumulation of mutations and epimutations. Here, we first review current concepts regarding the relationship between DNA damage, repair, and mutation, as well as the data regarding genome alterations as a function of age. We then describe a model for how randomly induced DNA sequence and epigenomic variants in the somatic genomes of animals can result in functional decline and disease in old age. Finally, we discuss the genetics of genome instability in relation to longevity to address the importance of alterations in the somatic genome as a causal factor in aging and to underscore the opportunities provided by genetic approaches to develop interventions that attenuate genome instability, reduce disease risk, and increase life span.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Hoeijmakers JH: DNA damage, aging, and cancer. N Engl J Med 2009. (PMID 19812404) [PubMed] [DOI]

- ↑ Blackburn EH et al.: Telomeres and telomerase: the path from maize, Tetrahymena and yeast to human cancer and aging. Nat Med 2006. (PMID 17024208) [PubMed] [DOI]

- ↑ Palm W & de Lange T: How shelterin protects mammalian telomeres. Annu Rev Genet 2008. (PMID 18680434) [PubMed] [DOI] The genomes of prokaryotes and eukaryotic organelles are usually circular as are most plasmids and viral genomes. In contrast, the nuclear genomes of eukaryotes are organized on linear chromosomes, which require mechanisms to protect and replicate DNA ends. Eukaryotes navigate these problems with the advent of telomeres, protective nucleoprotein complexes at the ends of linear chromosomes, and telomerase, the enzyme that maintains the DNA in these structures. Mammalian telomeres contain a specific protein complex, shelterin, that functions to protect chromosome ends from all aspects of the DNA damage response and regulates telomere maintenance by telomerase. Recent experiments, discussed here, have revealed how shelterin represses the ATM and ATR kinase signaling pathways and hides chromosome ends from nonhomologous end joining and homology-directed repair.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Armanios M & Blackburn EH: The telomere syndromes. Nat Rev Genet 2012. (PMID 22965356) [PubMed] [DOI] [Full text] There has been mounting evidence of a causal role for telomere dysfunction in a number of degenerative disorders. Their manifestations encompass common disease states such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and bone marrow failure. Although these disorders seem to be clinically diverse, collectively they comprise a single syndrome spectrum defined by the short telomere defect. Here we review the manifestations and unique genetics of telomere syndromes. We also discuss their underlying molecular mechanisms and significance for understanding common age-related disease processes.

- ↑ Blasco MA: Telomere length, stem cells and aging. Nat Chem Biol 2007. (PMID 17876321) [PubMed] [DOI] Telomere shortening occurs concomitant with organismal aging, and it is accelerated in the context of human diseases associated with mutations in telomerase, such as some cases of dyskeratosis congenita, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and aplastic anemia. People with these diseases, as well as Terc-deficient mice, show decreased lifespan coincidental with a premature loss of tissue renewal, which suggests that telomerase is rate-limiting for tissue homeostasis and organismal survival. These findings have gained special relevance as they suggest that telomerase activity and telomere length can directly affect the ability of stem cells to regenerate tissues. If this is true, stem cell dysfunction provoked by telomere shortening may be one of the mechanisms responsible for organismal aging in both humans and mice. Here, we will review the current evidence linking telomere shortening to aging and stem cell dysfunction.

- ↑ Fumagalli M et al.: Telomeric DNA damage is irreparable and causes persistent DNA-damage-response activation. Nat Cell Biol 2012. (PMID 22426077) [PubMed] [DOI] [Full text] The DNA-damage response (DDR) arrests cell-cycle progression until damage is removed. DNA-damage-induced cellular senescence is associated with persistent DDR. The molecular bases that distinguish transient from persistent DDR are unknown. Here we show that a large fraction of exogenously induced persistent DDR markers is associated with telomeric DNA in cultured cells and mammalian tissues. In yeast, a chromosomal DNA double-strand break next to a telomeric sequence resists repair and impairs DNA ligase 4 recruitment. In mammalian cells, ectopic localization of telomeric factor TRF2 next to a double-strand break induces persistent DNA damage and DDR. Linear, but not circular, telomeric DNA or scrambled DNA induces a prolonged checkpoint in normal cells. In terminally differentiated tissues of old primates, DDR markers accumulate at telomeres that are not critically short. We propose that linear genomes are not uniformly reparable and that telomeric DNA tracts, if damaged, are irreparable and trigger persistent DDR and cellular senescence.

- ↑ Jaskelioff M et al.: Telomerase reactivation reverses tissue degeneration in aged telomerase-deficient mice. Nature 2011. (PMID 21113150) [PubMed] [DOI] [Full text] An ageing world population has fuelled interest in regenerative remedies that may stem declining organ function and maintain fitness. Unanswered is whether elimination of intrinsic instigators driving age-associated degeneration can reverse, as opposed to simply arrest, various afflictions of the aged. Such instigators include progressively damaged genomes. Telomerase-deficient mice have served as a model system to study the adverse cellular and organismal consequences of wide-spread endogenous DNA damage signalling activation in vivo. Telomere loss and uncapping provokes progressive tissue atrophy, stem cell depletion, organ system failure and impaired tissue injury responses. Here, we sought to determine whether entrenched multi-system degeneration in adult mice with severe telomere dysfunction can be halted or possibly reversed by reactivation of endogenous telomerase activity. To this end, we engineered a knock-in allele encoding a 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT)-inducible telomerase reverse transcriptase-oestrogen receptor (TERT-ER) under transcriptional control of the endogenous TERT promoter. Homozygous TERT-ER mice have short dysfunctional telomeres and sustain increased DNA damage signalling and classical degenerative phenotypes upon successive generational matings and advancing age. Telomerase reactivation in such late generation TERT-ER mice extends telomeres, reduces DNA damage signalling and associated cellular checkpoint responses, allows resumption of proliferation in quiescent cultures, and eliminates degenerative phenotypes across multiple organs including testes, spleens and intestines. Notably, somatic telomerase reactivation reversed neurodegeneration with restoration of proliferating Sox2(+) neural progenitors, Dcx(+) newborn neurons, and Olig2(+) oligodendrocyte populations. Consistent with the integral role of subventricular zone neural progenitors in generation and maintenance of olfactory bulb interneurons, this wave of telomerase-dependent neurogenesis resulted in alleviation of hyposmia and recovery of innate olfactory avoidance responses. Accumulating evidence implicating telomere damage as a driver of age-associated organ decline and disease risk and the marked reversal of systemic degenerative phenotypes in adult mice observed here support the development of regenerative strategies designed to restore telomere integrity.

- ↑ Bernardes de Jesus B et al.: Telomerase gene therapy in adult and old mice delays aging and increases longevity without increasing cancer. EMBO Mol Med 2012. (PMID 22585399) [PubMed] [DOI] [Full text] A major goal in aging research is to improve health during aging. In the case of mice, genetic manipulations that shorten or lengthen telomeres result, respectively, in decreased or increased longevity. Based on this, we have tested the effects of a telomerase gene therapy in adult (1 year of age) and old (2 years of age) mice. Treatment of 1- and 2-year old mice with an adeno associated virus (AAV) of wide tropism expressing mouse TERT had remarkable beneficial effects on health and fitness, including insulin sensitivity, osteoporosis, neuromuscular coordination and several molecular biomarkers of aging. Importantly, telomerase-treated mice did not develop more cancer than their control littermates, suggesting that the known tumorigenic activity of telomerase is severely decreased when expressed in adult or old organisms using AAV vectors. Finally, telomerase-treated mice, both at 1-year and at 2-year of age, had an increase in median lifespan of 24 and 13%, respectively. These beneficial effects were not observed with a catalytically inactive TERT, demonstrating that they require telomerase activity. Together, these results constitute a proof-of-principle of a role of TERT in delaying physiological aging and extending longevity in normal mice through a telomerase-based treatment, and demonstrate the feasibility of anti-aging gene therapy.

- ↑ Kouzarides T: Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell 2007. (PMID 17320507) [PubMed] [DOI] The surface of nucleosomes is studded with a multiplicity of modifications. At least eight different classes have been characterized to date and many different sites have been identified for each class. Operationally, modifications function either by disrupting chromatin contacts or by affecting the recruitment of nonhistone proteins to chromatin. Their presence on histones can dictate the higher-order chromatin structure in which DNA is packaged and can orchestrate the ordered recruitment of enzyme complexes to manipulate DNA. In this way, histone modifications have the potential to influence many fundamental biological processes, some of which may be epigenetically inherited.

- ↑ Mostoslavsky R et al.: Genomic instability and aging-like phenotype in the absence of mammalian SIRT6. Cell 2006. (PMID 16439206) [PubMed] [DOI] The Sir2 histone deacetylase functions as a chromatin silencer to regulate recombination, genomic stability, and aging in budding yeast. Seven mammalian Sir2 homologs have been identified (SIRT1-SIRT7), and it has been speculated that some may have similar functions to Sir2. Here, we demonstrate that SIRT6 is a nuclear, chromatin-associated protein that promotes resistance to DNA damage and suppresses genomic instability in mouse cells, in association with a role in base excision repair (BER). SIRT6-deficient mice are small and at 2-3 weeks of age develop abnormalities that include profound lymphopenia, loss of subcutaneous fat, lordokyphosis, and severe metabolic defects, eventually dying at about 4 weeks. We conclude that one function of SIRT6 is to promote normal DNA repair, and that SIRT6 loss leads to abnormalities in mice that overlap with aging-associated degenerative processes.

- ↑ Herranz D et al.: Sirt1 improves healthy ageing and protects from metabolic syndrome-associated cancer. Nat Commun 2010. (PMID 20975665) [PubMed] [DOI] [Full text] Genetic overexpression of protein deacetylase Sir2 increases longevity in a variety of lower organisms, and this has prompted interest in the effects of its closest mammalian homologue, Sirt1, on ageing and cancer. We have generated transgenic mice moderately overexpressing Sirt1 under its own regulatory elements (Sirt1-tg). Old Sirt1-tg mice present lower levels of DNA damage, decreased expression of the ageing-associated gene p16(Ink4a), a better general health and fewer spontaneous carcinomas and sarcomas. These effects, however, were not sufficiently potent to affect longevity. To further extend these observations, we developed a metabolic syndrome-associated liver cancer model in which wild-type mice develop multiple carcinomas. Sirt1-tg mice show a reduced susceptibility to liver cancer and exhibit improved hepatic protection from both DNA damage and metabolic damage. Together, these results provide direct proof of the anti-ageing activity of Sirt1 in mammals and of its tumour suppression activity in ageing- and metabolic syndrome-associated cancer.

- ↑ Brown K et al.: SIRT3 reverses aging-associated degeneration. Cell Rep 2013. (PMID 23375372) [PubMed] [DOI] [Full text] Despite recent controversy about their function in some organisms, sirtuins are thought to play evolutionarily conserved roles in lifespan extension. Whether sirtuins can reverse aging-associated degeneration is unknown. Tissue-specific stem cells persist throughout the entire lifespan to repair and maintain tissues, but their self-renewal and differentiation potential become dysregulated with aging. We show that SIRT3, a mammalian sirtuin that regulates the global acetylation landscape of mitochondrial proteins and reduces oxidative stress, is highly enriched in hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) where it regulates a stress response. SIRT3 is dispensable for HSC maintenance and tissue homeostasis at a young age under homeostatic conditions but is essential under stress or at an old age. Importantly, SIRT3 is suppressed with aging, and SIRT3 upregulation in aged HSCs improves their regenerative capacity. Our study illuminates the plasticity of mitochondrial homeostasis controlling stem cell and tissue maintenance during the aging process and shows that aging-associated degeneration can be reversed by a sirtuin.

- ↑ Kanfi Y et al.: The sirtuin SIRT6 regulates lifespan in male mice. Nature 2012. (PMID 22367546) [PubMed] [DOI] The significant increase in human lifespan during the past century confronts us with great medical challenges. To meet these challenges, the mechanisms that determine healthy ageing must be understood and controlled. Sirtuins are highly conserved deacetylases that have been shown to regulate lifespan in yeast, nematodes and fruitflies. However, the role of sirtuins in regulating worm and fly lifespan has recently become controversial. Moreover, the role of the seven mammalian sirtuins, SIRT1 to SIRT7 (homologues of the yeast sirtuin Sir2), in regulating lifespan is unclear. Here we show that male, but not female, transgenic mice overexpressing Sirt6 (ref. 4) have a significantly longer lifespan than wild-type mice. Gene expression analysis revealed significant differences between male Sirt6-transgenic mice and male wild-type mice: transgenic males displayed lower serum levels of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1), higher levels of IGF-binding protein 1 and altered phosphorylation levels of major components of IGF1 signalling, a key pathway in the regulation of lifespan. This study shows the regulation of mammalian lifespan by a sirtuin family member and has important therapeutic implications for age-related diseases.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 25.4 Larson K et al.: Heterochromatin formation promotes longevity and represses ribosomal RNA synthesis. PLoS Genet 2012. (PMID 22291607) [PubMed] [DOI] [Full text] Organismal aging is influenced by a multitude of intrinsic and extrinsic factors, and heterochromatin loss has been proposed to be one of the causes of aging. However, the role of heterochromatin in animal aging has been controversial. Here we show that heterochromatin formation prolongs lifespan and controls ribosomal RNA synthesis in Drosophila. Animals with decreased heterochromatin levels exhibit a dramatic shortening of lifespan, whereas increasing heterochromatin prolongs lifespan. The changes in lifespan are associated with changes in muscle integrity. Furthermore, we show that heterochromatin levels decrease with normal aging and that heterochromatin formation is essential for silencing rRNA transcription. Loss of epigenetic silencing and loss of stability of the rDNA locus have previously been implicated in aging of yeast. Taken together, these results suggest that epigenetic preservation of genome stability, especially at the rDNA locus, and repression of unnecessary rRNA synthesis, might be an evolutionarily conserved mechanism for prolonging lifespan.

- ↑ Wilson VL et al.: Genomic 5-methyldeoxycytidine decreases with age. J Biol Chem 1987. (PMID 3611071) [PubMed] Significant losses of DNA 5-methyldeoxycytidine residues in old age could disrupt cellular gene expression and contribute to the physiological decline of the animal. Thus, the 5-methyldeoxycytidine content of DNAs, isolated from the tissues of two rodent species of various ages, were determined. Mus musculus lost DNA methylation sites at a rate of about 4.7 X 10(4) (approximately 0.012% of the newborn level)/month. Peromyscus leucopus lost DNA 5-methyldeoxycytidine residues at a rate of only 2.3 X 10(4) (approximately 0.006% of the newborn level)/month. Since P. leucopus generally live twice as long as M. musculus, the rate of loss of DNA 5-methyldeoxycytidine residues appears to be inversely related to life span. Similar losses in genomic 5-methyldeoxycytidine content were also observed to correlate with donor age in cultured normal human bronchial epithelial cells.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Heyn H et al.: Distinct DNA methylomes of newborns and centenarians. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012. (PMID 22689993) [PubMed] [DOI] [Full text] Human aging cannot be fully understood in terms of the constrained genetic setting. Epigenetic drift is an alternative means of explaining age-associated alterations. To address this issue, we performed whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) of newborn and centenarian genomes. The centenarian DNA had a lower DNA methylation content and a reduced correlation in the methylation status of neighboring cytosine--phosphate--guanine (CpGs) throughout the genome in comparison with the more homogeneously methylated newborn DNA. The more hypomethylated CpGs observed in the centenarian DNA compared with the neonate covered all genomic compartments, such as promoters, exonic, intronic, and intergenic regions. For regulatory regions, the most hypomethylated sequences in the centenarian DNA were present mainly at CpG-poor promoters and in tissue-specific genes, whereas a greater level of DNA methylation was observed in CpG island promoters. We extended the study to a larger cohort of newborn and nonagenarian samples using a 450,000 CpG-site DNA methylation microarray that reinforced the observation of more hypomethylated DNA sequences in the advanced age group. WGBS and 450,000 analyses of middle-age individuals demonstrated DNA methylomes in the crossroad between the newborn and the nonagenarian/centenarian groups. Our study constitutes a unique DNA methylation analysis of the extreme points of human life at a single-nucleotide resolution level.

- ↑ Zhang J et al.: Highly enriched BEND3 prevents the premature activation of bivalent genes during differentiation. Science 2022. (PMID 35143257) [PubMed] [DOI] Bivalent genes are ready for activation upon the arrival of developmental cues. Here, we report that BEND3 is a CpG island (CGI)-binding protein that is enriched at regulatory elements. The cocrystal structure of BEND3 in complex with its target DNA reveals the structural basis for its DNA methylation-sensitive binding property. Mouse embryos ablated of Bend3 died at the pregastrulation stage. Bend3 null embryonic stem cells (ESCs) exhibited severe defects in differentiation, during which hundreds of CGI-containing bivalent genes were prematurely activated. BEND3 is required for the stable association of polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) at bivalent genes that are highly occupied by BEND3, which suggests a reining function of BEND3 in maintaining high levels of H3K27me3 at these bivalent genes in ESCs to prevent their premature activation in the forthcoming developmental stage.

- ↑ Seale K et al.: Making sense of the ageing methylome. Nat Rev Genet 2022. (PMID 35501397) [PubMed] [DOI] [Full text] Over time, the human DNA methylation landscape accrues substantial damage, which has been associated with a broad range of age-related diseases, including cardiovascular disease and cancer. Various age-related DNA methylation changes have been described, including at the level of individual CpGs, such as differential and variable methylation, and at the level of the whole methylome, including entropy and correlation networks. Here, we review these changes in the ageing methylome as well as the statistical tools that can be used to quantify them. We detail the evidence linking DNA methylation to ageing phenotypes and the longevity strategies aimed at altering both DNA methylation patterns and machinery to extend healthspan and lifespan. Lastly, we discuss theories on the mechanistic causes of epigenetic ageing.

- ↑ Osorio FG et al.: Nuclear envelope alterations generate an aging-like epigenetic pattern in mice deficient in Zmpste24 metalloprotease. Aging Cell 2010. (PMID 20961378) [PubMed] [DOI] Mutations in the nuclear envelope protein lamin A or in its processing protease ZMPSTE24 cause human accelerated aging syndromes, including Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Similarly, Zmpste24-deficient mice accumulate unprocessed prelamin A and develop multiple progeroid symptoms, thus representing a valuable animal model for the study of these syndromes. Zmpste24-deficient mice also show marked transcriptional alterations associated with chromatin disorganization, but the molecular links between both processes are unknown. We report herein that Zmpste24-deficient mice show a hypermethylation of rDNA that reduces the transcription of ribosomal genes, being this reduction reversible upon treatment with DNA methyltransferase inhibitors. This alteration has been previously described during physiological aging in rodents, suggesting its potential role in the development of the progeroid phenotypes. We also show that Zmpste24-deficient mice present global hypoacetylation of histones H2B and H4. By using a combination of RNA sequencing and chromatin immunoprecipitation assays, we demonstrate that these histone modifications are associated with changes in the expression of several genes involved in the control of cell proliferation and metabolic processes, which may contribute to the plethora of progeroid symptoms exhibited by Zmpste24-deficient mice. The identification of these altered genes may help to clarify the molecular mechanisms underlying aging and progeroid syndromes as well as to define new targets for the treatment of these dramatic diseases.

- ↑ Shumaker DK et al.: Mutant nuclear lamin A leads to progressive alterations of epigenetic control in premature aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006. (PMID 16738054) [PubMed] [DOI] [Full text] The premature aging disease Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome (HGPS) is caused by a mutant lamin A (LADelta50). Nuclei in cells expressing LADelta50 are abnormally shaped and display a loss of heterochromatin. To determine the mechanisms responsible for the loss of heterochromatin, epigenetic marks regulating either facultative or constitutive heterochromatin were examined. In cells from a female HGPS patient, histone H3 trimethylated on lysine 27 (H3K27me3), a mark for facultative heterochromatin, is lost on the inactive X chromosome (Xi). The methyltransferase responsible for this mark, EZH2, is also down-regulated. These alterations are detectable before the changes in nuclear shape that are considered to be the pathological hallmarks of HGPS cells. The results also show a down-regulation of the pericentric constitutive heterochromatin mark, histone H3 trimethylated on lysine 9, and an altered association of this mark with heterochromatin protein 1alpha (Hp1alpha) and the CREST antigen. This loss of constitutive heterochromatin is accompanied by an up-regulation of pericentric satellite III repeat transcripts. In contrast to these decreases in histone H3 methylation states, there is an increase in the trimethylation of histone H4K20, an epigenetic mark for constitutive heterochromatin. Expression of LADelta50 in normal cells induces changes in histone methylation patterns similar to those seen in HGPS cells. The epigenetic changes described most likely represent molecular mechanisms responsible for the rapid progression of premature aging in HGPS patients.

- ↑ Dang W et al.: Histone H4 lysine 16 acetylation regulates cellular lifespan. Nature 2009. (PMID 19516333) [PubMed] [DOI] [Full text] Cells undergoing developmental processes are characterized by persistent non-genetic alterations in chromatin, termed epigenetic changes, represented by distinct patterns of DNA methylation and histone post-translational modifications. Sirtuins, a group of conserved NAD(+)-dependent deacetylases or ADP-ribosyltransferases, promote longevity in diverse organisms; however, their molecular mechanisms in ageing regulation remain poorly understood. Yeast Sir2, the first member of the family to be found, establishes and maintains chromatin silencing by removing histone H4 lysine 16 acetylation and bringing in other silencing proteins. Here we report an age-associated decrease in Sir2 protein abundance accompanied by an increase in H4 lysine 16 acetylation and loss of histones at specific subtelomeric regions in replicatively old yeast cells, which results in compromised transcriptional silencing at these loci. Antagonizing activities of Sir2 and Sas2, a histone acetyltransferase, regulate the replicative lifespan through histone H4 lysine 16 at subtelomeric regions. This pathway, distinct from existing ageing models for yeast, may represent an evolutionarily conserved function of sirtuins in regulation of replicative ageing by maintenance of intact telomeric chromatin.

- ↑ Hu Z et al.: Nucleosome loss leads to global transcriptional up-regulation and genomic instability during yeast aging. Genes Dev 2014. (PMID 24532716) [PubMed] [DOI] [Full text] All eukaryotic cells divide a finite number of times, although the mechanistic basis of this replicative aging remains unclear. Replicative aging is accompanied by a reduction in histone protein levels, and this is a cause of aging in budding yeast. Here we show that nucleosome occupancy decreased by 50% across the whole genome during replicative aging using spike-in controlled micrococcal nuclease digestion followed by sequencing. Furthermore, nucleosomes became less well positioned or moved to sequences predicted to better accommodate histone octamers. The loss of histones during aging led to transcriptional induction of all yeast genes. Genes that are normally repressed by promoter nucleosomes were most induced, accompanied by preferential nucleosome loss from their promoters. We also found elevated levels of DNA strand breaks, mitochondrial DNA transfer to the nuclear genome, large-scale chromosomal alterations, translocations, and retrotransposition during aging.

- ↑ O'Sullivan RJ et al.: Reduced histone biosynthesis and chromatin changes arising from a damage signal at telomeres. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2010. (PMID 20890289) [PubMed] [DOI] [Full text] During replicative aging of primary cells morphological transformations occur, the expression pattern is altered and chromatin changes globally. Here we show that chronic damage signals, probably caused by telomere processing, affect expression of histones and lead to their depletion. We investigated the abundance and cell cycle expression of histones and histone chaperones and found defects in histone biosynthesis during replicative aging. Simultaneously, epigenetic marks were redistributed across the phases of the cell cycle and the DNA damage response (DDR) machinery was activated. The age-dependent reprogramming affected telomeric chromatin itself, which was progressively destabilized, leading to a boost of the telomere-associated DDR with each successive cell cycle. We propose a mechanism in which changes in the structural and epigenetic integrity of telomeres affect core histones and their chaperones, enforcing a self-perpetuating pathway of global epigenetic changes that ultimately leads to senescence.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Pegoraro G et al.: Ageing-related chromatin defects through loss of the NURD complex. Nat Cell Biol 2009. (PMID 19734887) [PubMed] [DOI] [Full text] Physiological and premature ageing are characterized by multiple defects in chromatin structure and accumulation of persistent DNA damage. Here we identify the NURD chromatin remodelling complex as a key modulator of these ageing-associated chromatin defects. We demonstrate loss of several NURD components during premature and normal ageing and we find an ageing-associated reduction in HDAC1 activity. Silencing of individual NURD subunits recapitulated chromatin defects associated with ageing and we provide evidence that structural chromatin defects precede DNA damage accumulation. These results outline a molecular mechanism for chromatin defects during ageing.

- ↑ Tsurumi A & Li WX: Global heterochromatin loss: a unifying theory of aging?. Epigenetics 2012. (PMID 22647267) [PubMed] [DOI] [Full text] The aging field is replete with theories. Over the past years, many distinct, yet overlapping mechanisms have been proposed to explain organismal aging. These include free radicals, loss of heterochromatin, genetically programmed senescence, telomere shortening, genomic instability, nutritional intake and growth signaling, to name a few. The objective of this Point-of-View is to highlight recent progress on the "loss of heterochromatin" model of aging and to propose that epigenetic changes contributing to global heterochromatin loss may underlie the various cellular processes associated with aging.

- ↑ Researchers Propose Five New Hallmarks of Aging, https://www.lifespan.io/news/researchers-propose-five-new-hallmarks-of-aging/

- ↑ López-Otín C et al.: Hallmarks of aging: An expanding universe. Cell 2023. (PMID 36599349) [PubMed] [DOI] Aging is driven by hallmarks fulfilling the following three premises: (1) their age-associated manifestation, (2) the acceleration of aging by experimentally accentuating them, and (3) the opportunity to decelerate, stop, or reverse aging by therapeutic interventions on them. We propose the following twelve hallmarks of aging: genomic instability, telomere attrition, epigenetic alterations, loss of proteostasis, disabled macroautophagy, deregulated nutrient-sensing, mitochondrial dysfunction, cellular senescence, stem cell exhaustion, altered intercellular communication, chronic inflammation, and dysbiosis. These hallmarks are interconnected among each other, as well as to the recently proposed hallmarks of health, which include organizational features of spatial compartmentalization, maintenance of homeostasis, and adequate responses to stress.

- ↑ López-Otín C et al.: Meta-hallmarks of aging and cancer. Cell Metab 2023. (PMID 36599298) [PubMed] [DOI] Both aging and cancer are characterized by a series of partially overlapping "hallmarks" that we subject here to a meta-analysis. Several hallmarks of aging (i.e., genomic instability, epigenetic alterations, chronic inflammation, and dysbiosis) are very similar to specific cancer hallmarks and hence constitute common "meta-hallmarks," while other features of aging (i.e., telomere attrition and stem cell exhaustion) act likely to suppress oncogenesis and hence can be viewed as preponderantly "antagonistic hallmarks." Disabled macroautophagy and cellular senescence are two hallmarks of aging that exert context-dependent oncosuppressive and pro-tumorigenic effects. Similarly, the equivalence or antagonism between aging-associated deregulated nutrient-sensing and cancer-relevant alterations of cellular metabolism is complex. The agonistic and antagonistic relationship between the processes that drive aging and cancer has bearings for the age-related increase and oldest age-related decrease of cancer morbidity and mortality, as well as for the therapeutic management of malignant disease in the elderly.